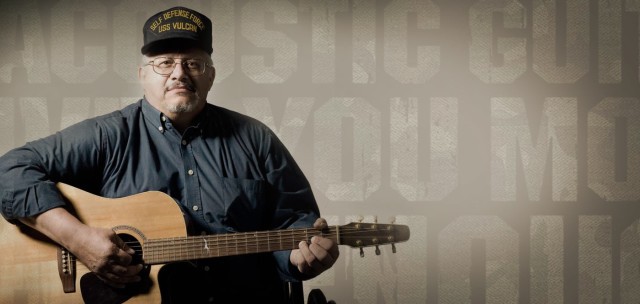

Dr. Warren L. Woodruff is a passionate music instructor

whose affection for classical music led to the creation of Dr. Fuddle and the

Gold Baton. We are honoured to be able to do an interview with someone of such

talent.

Welcome Warren.

Warren, how long have you been in the classical music industry?

I’ve been teaching for 26 years, but playing classical music for almost 40 years.

What inspired you to cross the boundaries from musician to author?

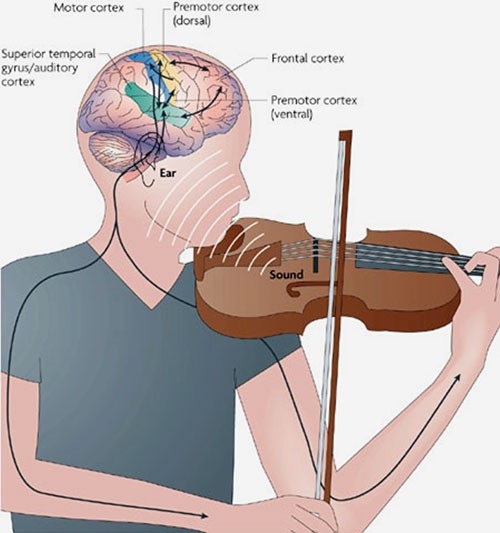

I’ve always wanted to inspire others through the joy of great music, not just through my many students, but in written word. I’ve also faced a lifelong challenge like Beethoven, a degenerative hearing disorder, which threatens my musical career, so I wanted to leave a written legacy, since I am not a genius composer like Beethoven.

Do you find the title of author to merely be an added side to your musical side or do you treat them as separate personas?

They are definitely separate personas. I will always be, first and foremost, a musician, even if my hearing disorder has other plans! But being an author is very important also. Other than writing the series of Dr. Fuddle novels, screenplays and picture books, I have many other written projects I would like to complete, all of them musically oriented, except for one, an unpublished manuscript on religious philosophy.

What is your goal behind this novel of Dr. Fuddle and the Gold Baton?

My goal is to create something classic and very different in today’s market--not something that will just be “hot” for a few years and forgotten. The driving force behind each story is mystery and adventure, to engage and entertain young readers. But I also want to pique their interest in music, particularly classical music, INSPIRE them to excellence, and to find their lifelong passion, as I found mine at a very early age.

From the synopsis I was provided the novel seems to create an adventurous flow between music and an exciting storyline. Can you please tell our readers a bit more? What can they expect from reading it?

They can expect a very fun reading experience, even if they have no knowledge of classical music. This book is not an educational tool to promote my art form. It is an adventure from beginning to end, which happens to be set in the musical, magical land of Orphea. They can also expect to feel a longing to hear the music described in the book and a desire to see the whole story played out as a major motion picture, which is in development.

Does the novel contain some of the beautiful sketches that are beside your characters on your blog?

Yes. All of the artwork is incorporated into the book at the appropriate places in the storyline.

What age group and genre are you targeting?

This first book, middle grade, from 6th-8th grade, but I’m quickly getting feedback that my adult readers are enjoying it every bit as much as the target age group, just like the HARRY POTTER series. As my series continues, the protagonists will age, and the target age group will become Young Adult.

We had thousands of downloads the first weekend and have already gotten twenty-three five star reviews, plus feedback from many readers saying they can’t wait to see the movie!

From a little googling I noticed that there is also mention of another novel called First Lady of the Organ, Diane Bish: A Biography can you give our readers a bit more insight to the novel.

This biography was an extension of my Ph.D. dissertation on the most important and visible female organist in history. She is still alive, performing and signing these biographies at her concerts. The book was self-published in 1994, but is still selling. Talk about a project with longevity!

Where can people find your works?

Right now, DR. FUDDLE AND THE GOLD BATON is available exclusively as an e-book for one year at Amazon.com, but the hard copies are also available at Amazon, and other web stores. Autographed copies will be available through drfuddle.com and drfuddlesmusicalblog.blogspot.com.

Are you working on anything else currently that we should be on the lookout for?

Yes. I’m working on the next book in the Fuddle series, which will be a prequel to the first book, the back story of how things “got to how they got in Orphea” in the first novel. I’m also redrafting my stage play entitled BEETHOVEN. The dramatic rights will be made available to smaller, off-Broadway type venues. It is the moving account of the life of Beethoven, my greatest hero, in six scenes, with narration and music. Eventually, when the timing is right, I will publish my book on religious philosophy.

How has your journey been on becoming an author?

From a general public perspective I always assumed it was something easy. You write and then you send it in, if people like it they go for it, if they don’t you try someone else. The perception is not at all the case, writing in its own sense is an art.

I’ve mostly just written with ease from the heart in a state of inspiration. Oftentimes the writing experience has seemed--for lack of a better word--supernatural. Parts of DR. FUDDLE AND THE GOLD BATON felt as though I was receiving the words from an unseen source, like it was writing itself. This was particularly true of my book on religious philosophy, too, as though my fingers were moving rapidly on the keys, like an automatic dictation for hours on end, as strange as they may sound. But there were also some times, not often, where writing just seemed like hard work.

Do you have any messages that you would like to leave our audience with?

Open your hearts, minds and imaginations to the totally new world of Dr. Fuddle and Orphea! Be ready to experience literature and music in a way you never dreamed possible.

Thanks so much for taking the time to do this small

interview. We wish you well in all your future endeavors.

Read more

Read more

.jpg)