Showing posts with label Franz Liszt. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Franz Liszt. Show all posts

The Composer and his Muse: Franz Liszt and Caroline de Saint-Cricq First Love

After Adam Liszt’s death in Bologne-sur-mer in 1827, Franz Liszt met his mother in Paris where they settled down. Liszt, at sixteen, was now the breadwinner of the Liszt family. In order to earn regular income for his mother and himself, Liszt became a piano teacher in Paris for the aristocracy. was sixteen when she met Liszt. He became her piano teacher, and the two quickly fell in love.

Caroline’s lessons were supervised by her mother. Additionally, her mother approved of the relationship. After becoming ill quite quickly in 1828, she told the Count from her deathbed: “If she loves him, let her be happy." The Count likely thought these words were demented mutterings of a woman at death’s door. He probably did not take this comment seriously and therefore was not fully aware of the relationship blooming between Liszt and his student. Caroline’s mother died in June of 1828.

Though the lessons were postponed due to a period of mourning, Liszt continued to stop by the Saint-Cricq home to check on the grieving Caroline. Their lessons resumed, according to Sitwell, the death of Caroline’s mother may have been an excuse to continue lessons as a distraction. The Count was often away on government business, and as such the young couple spent time together daily without supervision. Zsolt Harsányi in his book, Immortal Franz: the Life and Loves of Franz Liszt, mentions an aunt who supervised at first, but their gradually extending lessons tired her and she left the two young people alone.

On one fateful occasion, Liszt stayed conversing on topics such as music, poetry, and religion with Caroline past midnight. He had an encounter with the porter of the Saint-Cricq building when he needed to be let out. Adam Walker claims that Liszt was ignorant of the need to fill the porter’s purse in order to remain anonymous. Derek Watson, alternatively, says that Liszt failed to tip the butler who complained to the Count of the late hour. Either way, the servant in question informed Pierre de Saint-Cricq of this occurrence, and the Count met Liszt the next time the musician stopped by. After reminding Liszt of the difference in class between Caroline and himself, the Count ended the lessons and told Liszt that he was not to return to their household, nor see his daughter again. This class difference was already chafing at Liszt, so it was probably a heavy blow.

From the end of the affair in 1828 to about the time of the July Revolution of 1830, Liszt was depressed and ill. He was mistakenly pronounced dead in October of 1828 by an article published in Le Corsaire.

Liszt was certainly not dead, but his romantic relationship with Caroline de Saint-Cricq was over. Though she played an absent role in his life as the symbol of his first love, he only saw her once again in 1844, at her home in Pau, France. He wrote "Ich möchte hingehn" (I would like to go away), later, inspired by their reunion. According to Adrian Williams, she said that Liszt was the “single shining star” of her life.

Read more

The Composer and His Muse: Liszt and The Countess d'Agoult

Liszt was in the bloom of youth and of rising fame when he made the acquaintance of the woman to whom his life was to be linked for ten years. The only love affair that produced children (Blandine, Cosima, Daniel). D’Agoult and Liszt met in 1833 at a musical gathering hosted by Marquise Le Vayer. The chemistry was unmistakable. Marie was six years older than the young enchanter, and by the early summer of 1833 their affair was in full bloom.

Liszt visited her in Croissy, and Marie came to Paris where they secretly met in a small apartment affectionately referred to as the “rat hole.” Such was the woman who, captivated by the youth and talent of the Hungarian virtuoso, abandoned for him husband and child, and, sacrificing position, reputation and fortune to her passion, was for ten years the faithful companion of his travels all over Europe.

Following the tragic death of her daughter Louise, Marie d’Agoult found herself pregnant with Franz Liszt’s child. Since she was still married to Charles d’Agoult, it was impossible to stay in Paris. She wrote her husband in May 1835, telling him that their marriage was over. In order to avoid the scandal, which was hardly possible, the lovers made secret arrangements to elope to Switzerland. Parisian society was dumbfounded that a very prominent and beautiful Comtesse should leave her husband for a traveling pianist, and in the public eye the whole affair was branded a flagrant case of abduction. Nevertheless, the couple left for Basle and since Charles d’Agoult had obtained a legal separation from his wife.

She became close to Liszt's circle of friends, including Frédéric Chopin, who dedicated his 12 Études, Op. 25 to her (his earlier set of 12 Études, Op. 10 had been dedicated to Liszt).

Liszt's "Die Lorelei," one of his very first songs, based on text by Heinrich Heine, was also dedicated to her. D'Agoult had three children with Liszt; however, she and Liszt did not marry, maintaining their independent views and other differences while Liszt was busy composing and touring throughout Europe.

The two left Paris for Switzerland in May of that year. Took a trip to Italy in 1837 as an established couple. Also visited George Sand at her home. Both Blandine and Cosima were quietly born out of the country under fabricated birth certificates. 1838, Suttoni claims is the beginning of the end of their relationship (on happy terms, anyway). Daniel was born in May 1839, in November of that year Liszt would embark on a series of performance tours throughout Europe. Touring and absences led to the final end of their relationship in 1844.

Besides many critical contributions on music, painting and sculpture, the Countess tried her hand at political economy and philosophy. In 1845, just about the time she broke off her liaison with Liszt, Madame d'Agoult entered the arena of politics.

Between 1835 and 1836, Liszt composed a collection of pieces entitled “Album d’un voyageur,” which was eventually published in 1842. After some major revisions, the majority of these compositions reappeared in a collection of three suites entitled “Années de pèlerinage.” And the first volume, entitled “Première année: Suisse,” contains a variety of musical, emotional and pictorial impressions from his time spend in Switzerland. Liszt suggested that in this collection “I have tried to portray in music a few of my strongest sensations and most lively impression.”

Read more

The Composer and his Muse: Franz Liszt and Caroline de Saint-Cricq First Love

After Adam Liszt’s death in Bologne-sur-mer in 1827, Franz Liszt met his mother in Paris where they settled down. Liszt, at sixteen, was now the breadwinner of the Liszt family. In order to earn regular income for his mother and himself, Liszt became a piano teacher in Paris for the aristocracy. was sixteen when she met Liszt. He became her piano teacher, and the two quickly fell in love.

Caroline’s lessons were supervised by her mother. Additionally, her mother approved of the relationship. After becoming ill quite quickly in 1828, she told the Count from her deathbed: “If she loves him, let her be happy." The Count likely thought these words were demented mutterings of a woman at death’s door. He probably did not take this comment seriously and therefore was not fully aware of the relationship blooming between Liszt and his student. Caroline’s mother died in June of 1828.

Though the lessons were postponed due to a period of mourning, Liszt continued to stop by the Saint-Cricq home to check on the grieving Caroline. Their lessons resumed, according to Sitwell, the death of Caroline’s mother may have been an excuse to continue lessons as a distraction. The Count was often away on government business, and as such the young couple spent time together daily without supervision. Zsolt Harsányi in his book, Immortal Franz: the Life and Loves of Franz Liszt, mentions an aunt who supervised at first, but their gradually extending lessons tired her and she left the two young people alone.

On one fateful occasion, Liszt stayed conversing on topics such as music, poetry, and religion with Caroline past midnight. He had an encounter with the porter of the Saint-Cricq building when he needed to be let out. Adam Walker claims that Liszt was ignorant of the need to fill the porter’s purse in order to remain anonymous. Derek Watson, alternatively, says that Liszt failed to tip the butler who complained to the Count of the late hour. Either way, the servant in question informed Pierre de Saint-Cricq of this occurrence, and the Count met Liszt the next time the musician stopped by. After reminding Liszt of the difference in class between Caroline and himself, the Count ended the lessons and told Liszt that he was not to return to their household, nor see his daughter again. This class difference was already chafing at Liszt, so it was probably a heavy blow.

From the end of the affair in 1828 to about the time of the July Revolution of 1830, Liszt was depressed and ill. He was mistakenly pronounced dead in October of 1828 by an article published in Le Corsaire.

Liszt was certainly not dead, but his romantic relationship with Caroline de Saint-Cricq was over. Though she played an absent role in his life as the symbol of his first love, he only saw her once again in 1844, at her home in Pau, France. He wrote "Ich möchte hingehn" (I would like to go away), later, inspired by their reunion. According to Adrian Williams, she said that Liszt was the “single shining star” of her life.

Read more

More Greatest Pianists!

There are so many issues involved in choosing the top classical pianists. Should it be based on their technical ability, their reputation or following, the breadth of their repertoire or their improvisation talents? Then there’s the question of whether those pianists who played before we had recording equipment can legitimately be considered since we can’t actually hear their playing to compare it with others. On this last point, it seems entirely justified to do so, particularly in cases where an individual stands out in a period in which we know there were a great number of incredible talents, and if they gained an international reputation long before the time of modern media and communication. Read more

Here are some of the greatest piano icons that ever played!

Vladimir Ashkenazy (1937-)

Ashkenazy is one of the heavyweights of the classical music world. Having been born in Russia he now holds both Icelandic and Swiss citizenship and is still performing as a pianist and conductor around the world. In 1962 he was a joint winner of the International Tchaikovsky Competition (with John Ogden, see below) and the following year he left the USSR to live in London. His vast catalogue of recordings includes the complete piano works of Rachmaninov and Chopin, the complete sonatas of Beethoven, Mozart's piano concertos as well as works by Scriabin, Prokfiev and Brahms. He's worked with all the biggest names of the 20th century including conductors Georg Solti, Zubin Mehta and Bernard Haitink.

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) Poland’s most famous composer was also one of the great piano virtuosos of his day. The vast majority of his work was for solo piano and though there are no recordings of him playing (the earliest sound recordings are from the 1860s), one contemporary said: “One may say that Chopin is the creator of a school of piano and a school of composition. In truth, nothing equals the lightness, the sweetness with which the composer preludes on the piano; moreover nothing may be compared to his works full of originality, distinction and grace.”

Myra Hess (1890-1965)

Dame Myra Hess, as she eventually became, is famous not so much for winning a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music at the age of 12, nor of performing with the legendary conductor Sir Thomas Beecham when she was 17 – but for the series of concerts she gave at the National Gallery during WWII. During the war, London’s music venues were closed to avoid mass casualties if any were hit by bombs. Hess had the idea of using the Gallery to host lunchtime concerts. The series ran for six and a half years and Hess herself performed in 150 of them.

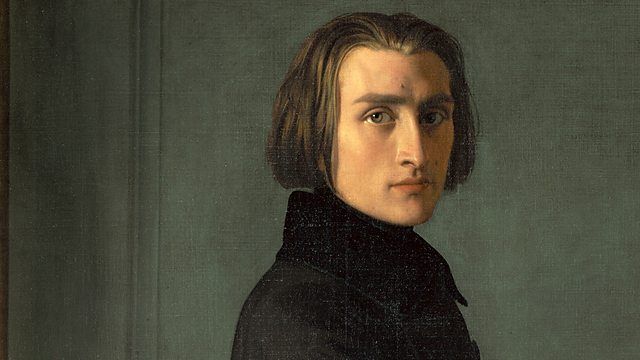

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Vying with Chopin for the crown of greatest 19th-century-virtuoso was Franz Liszt, the Hungarian composer, teacher and pianist. Among his best known works are his fiendishly difficult Années de pèlerinage, the Piano Sonata in B minor and his Mephisto Waltz. And as a performer his fame was legendary – there was even a word coined for the frenzy he inspired: Lisztomania. All eye-witness accounts of Liszt’s playing put him in the very first rank of classical pianists. Over an eight-year period of touring Europe in the early 1840s, he is estimated to have given over 1,000 performances. Part of the reason for his legendary status could be that he retired from performing at the relatively young age of 35 to concentrate on composing.

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

One of the few female pianists to compete in the largely male world of 19th-century music, Clara was a superstar of her day. Her talents far outshone those of her composer husband Robert. She wrote her own music as well – you can hear an example in the video below.

One critic of the time said: “The appearance of this artist can be regarded as epoch-making… In her creative hands, the most ordinary passage, the most routine motive acquires a significant meaning, a colour, which only those with the most consummate artistry can give.”

Claudio Arrau (1903-1991)

It’s said that this great Chilean pianist could read music before he could read words. It wasn’t long before he was playing works like the virtuosic Transcendental Etudes by Liszt. He’s perhaps best-known for his interpretations of the music of Beethoven. The legendary conductor Colin Davis said of Arrau: “His sound is amazing, and it is entirely his own… His devotion to Liszt is extraordinary. He ennobles that music in a way no one else in the world can.”

Read more

Lang Lang on Franz Liszt

Happy Birthday Franz Liszt Born Today in 1811

Excerpt from 2011 NPR Interview with Guy Raz:

RAZ: Lang Lang is a world-renowned concert pianist, and his love of Liszt is well-known. As a matter of fact, his new album is called "Liszt: My Piano Hero." He first heard Liszt's music as a 2-year-old while watching a famous television duo.

RAZ: Lang Lang is a world-renowned concert pianist, and his love of Liszt is well-known. As a matter of fact, his new album is called "Liszt: My Piano Hero." He first heard Liszt's music as a 2-year-old while watching a famous television duo.LANG LANG: "Tom and Jerry," and they were playing the Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, and I got fascinated.

RAZ: So you're watching "Tom and Jerry" play Liszt.

LANG: Yeah.

RAZ: Oh, actually, Liszt was playing behind them rather.

LANG: Yeah, and I thought it was such exciting music. So he really lead me into a professional pianist.

RAZ: What is it about Liszt's style that appeals to you so much as a performer?

LANG: He is a real piano god, so he make piano sound like entire orchestra. And he has this amazing technique like nobody else. At the same time, he brings passion and love and heart.

RAZ: You have said, Lang Lang, that as a composer, Liszt actually opened the door to modern music. How so?

LANG: The piano as an instrument was pretty weak that time. So Liszt is totally a monster at the piano. You know, he create such difficult pieces. So he always destroy pianos during the concerts.

RAZ: He actually destroyed them? He broke them?

LANG: Yeah. And because of his technique and his incredible power, piano as an instrument had a revolution and became much better instrument and much more solid.

RAZ: It's rare that Liszt comes up in, you know, top 10 lists of great composers of all time or - and I'm wondering why you think that is?

LANG: He focus a lot on piano music, not on many other instruments. Not like Beethoven or Mozart or Tchaikovsky, you know? They are more - they grow not only great piano work, but also symphonic work, tremor music - a bit like Paganini, you know? I mean, Paganini is famous for violin only, and Liszt is that type of composer - for piano

RAZ: And Paganini influenced Liszt's playing as well, right?

LANG: Absolutely. Liszt - when Liszt was a kid, he saw Paganini playing at violin, and he said that I'd like to be the Paganini on a piano.

RAZ: Some of this music sounds like actually - sounds like a workout. Does playing Liszt actually take a physical toll on you?

LANG: Absolutely. Playing Liszt, you need to put all your emotions and also very physical. I mean, his music - Paganini - it used La Campanella. It's very, very demanding. I mean, I exercise before I record this album.

RAZ: Lang Lang, I know you're performing Liszt's Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Philadelphia Orchestra tonight. And I'm looking through your - the liner notes of your new CD, and there's a photograph of you at the piano looking pretty good, man. You got like lasers coming out of your fingers at the piano. So I'm wondering, do you expect any Lang Lang-o-mania to break out tonight?

LANG: It will be quite hard, and the piece is very hard. So maybe you will see laser light but through music.

RAZ: You got any bodyguards on stage, or are there going to be, you know, audience members jumping up on stage to get locks of your hair?

LANG: Well, you know, for Philadelphia, I think we are pretty safe.

RAZ: That's Lang Lang. He's one of the most in demand concert pianists in the world. His new album is called "Liszt: My Piano Hero." And his hero, Franz Liszt, was born 200 years ago today. Lang Lang, thank you so much.

LANG: Thank you. Thank you, Guy.

Evgeny Kissin plays Valley d'Obermann by Franz Liszt on February 25 2011 at Boston Symphony Hall concert.

Vallée d'Obermann (Obermann's Valley) is the 6th suite from Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage) by Franz Liszt. It belongs to Première année: Suisse.

Dr. Fuddle's Top Ten Composers

7. Franz Liszt

(1811-1886), Hungarian romantic pianist and composer, most noted for being the first musical “superstar,” the greatest pianist of all time, creating some of the most demanding virtuoso piano music in the repertoire, such as the Sonata in b minor, the Mephisto Waltz, the Transcendental Etudes, Hungarian Rhapsodies; also noted for his development of the symphonic poem.

Listen to Nocturne in A flat Major No. 3 (Liebestraume - Dream of Love - Love Dreams) & Excerpts from Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C Sharp

(1811-1886), Hungarian romantic pianist and composer, most noted for being the first musical “superstar,” the greatest pianist of all time, creating some of the most demanding virtuoso piano music in the repertoire, such as the Sonata in b minor, the Mephisto Waltz, the Transcendental Etudes, Hungarian Rhapsodies; also noted for his development of the symphonic poem.

Listen to Nocturne in A flat Major No. 3 (Liebestraume - Dream of Love - Love Dreams) & Excerpts from Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C Sharp

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)