The Composer and his Muse: Franz Liszt and Caroline de Saint-Cricq First Love

After Adam Liszt’s death in Bologne-sur-mer in 1827, Franz Liszt met his mother in Paris where they settled down. Liszt, at sixteen, was now the breadwinner of the Liszt family. In order to earn regular income for his mother and himself, Liszt became a piano teacher in Paris for the aristocracy. was sixteen when she met Liszt. He became her piano teacher, and the two quickly fell in love.

Caroline’s lessons were supervised by her mother. Additionally, her mother approved of the relationship. After becoming ill quite quickly in 1828, she told the Count from her deathbed: “If she loves him, let her be happy." The Count likely thought these words were demented mutterings of a woman at death’s door. He probably did not take this comment seriously and therefore was not fully aware of the relationship blooming between Liszt and his student. Caroline’s mother died in June of 1828.

Though the lessons were postponed due to a period of mourning, Liszt continued to stop by the Saint-Cricq home to check on the grieving Caroline. Their lessons resumed, according to Sitwell, the death of Caroline’s mother may have been an excuse to continue lessons as a distraction. The Count was often away on government business, and as such the young couple spent time together daily without supervision. Zsolt Harsányi in his book, Immortal Franz: the Life and Loves of Franz Liszt, mentions an aunt who supervised at first, but their gradually extending lessons tired her and she left the two young people alone.

On one fateful occasion, Liszt stayed conversing on topics such as music, poetry, and religion with Caroline past midnight. He had an encounter with the porter of the Saint-Cricq building when he needed to be let out. Adam Walker claims that Liszt was ignorant of the need to fill the porter’s purse in order to remain anonymous. Derek Watson, alternatively, says that Liszt failed to tip the butler who complained to the Count of the late hour. Either way, the servant in question informed Pierre de Saint-Cricq of this occurrence, and the Count met Liszt the next time the musician stopped by. After reminding Liszt of the difference in class between Caroline and himself, the Count ended the lessons and told Liszt that he was not to return to their household, nor see his daughter again. This class difference was already chafing at Liszt, so it was probably a heavy blow.

From the end of the affair in 1828 to about the time of the July Revolution of 1830, Liszt was depressed and ill. He was mistakenly pronounced dead in October of 1828 by an article published in Le Corsaire.

Liszt was certainly not dead, but his romantic relationship with Caroline de Saint-Cricq was over. Though she played an absent role in his life as the symbol of his first love, he only saw her once again in 1844, at her home in Pau, France. He wrote "Ich möchte hingehn" (I would like to go away), later, inspired by their reunion. According to Adrian Williams, she said that Liszt was the “single shining star” of her life.

Read more

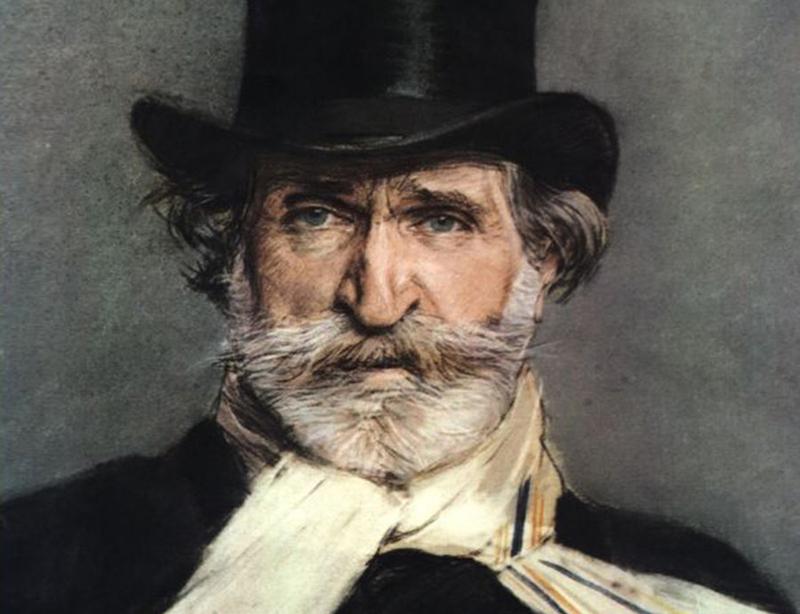

Happy Birthday Giuseppe Verdi the "King of Opera"

He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, and developed a musical education with the help of a local patron. Verdi came to dominate the Italian opera scene after the era of Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Gioachino Rossini, whose works significantly influenced him.

He struggled for success and in 1842, at age 28, it finally came with his bold new opera Nabucco, about the fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C. While the opera is justly famous for its moving chorus "Va, pensiero" — which became a rallying cry for Italy's struggle for independence and was sung spontaneously by a few hundred thousand people at Verdi's funeral in 1901 — it should be noted that the entire opera is a forward thrusting, rollicking affair. You would not be incorrect in describing it as "ass-kicking Verdi."

It's fun to trivialize Trovatore, Verdi's 18th opera, because of its outlandish plot. The Marx brothers spoofed it magnificently (but with a palpable appreciation) in their 1935 film A Night at the Opera. OK, so an old gypsy woman throws the wrong baby into the bonfire, setting off a string of unfortunate events. It could happen to anyone! Still, Trovatore is a treasure trove of some of Verdi's best and most hummable tunes, and they come lickety-split one after another. There's the crowd-pleasing "Anvil Chorus," plus "Di quella pira," with its brain-splitting high notes for the tenor, two gorgeous arias for soprano ("Tacea la notte" and "D'amor sull'ali rosee"), the exuberant "Stride la vampa" for the mezzo-soprano and "Il balen," a gorgeous moment of reflection for the baritone.

Verdi's operas act on deeply sociopolitical levels, and La Traviata is a perfect example. Here Verdi empowers the common individual. The opera stars a prostitute — something unheard of at the time — and she's the smartest, most sane and honest person in the opera. It takes very little imagination to see how this realistic story (nice boy falls in love with hooker, who breaks up with him to save his family's honor) dovetails with our contemporary concerns. La Traviata was also an act of daring for Verdi, a little jab at the conservatives of his native Parma who balked at the fact that he wasn't married to the woman he lived with. The lead soprano role is so multifaceted and difficult it almost requires three different types of sopranos to pull it off.

By the time Verdi wrote Simon Boccanegra, he was the king of opera. Even so, Boccanegra flopped at its 1857 premiere. (Verdi revised it successfully 24 years later.) It's not too nerdy to note that whatever one thinks of the convoluted plot (a 14th century doge, amid intense political maneuvering, manages to find his long-lost daughter), the work contains examples of two Verdi trademarks: The father-daughter duet and the "Verdi baritone." Verdi excelled at richly drawn, highly expressive roles for the baritone voice (Rigoletto, Falstaff, Macbeth, Iago, Nabucco) and Boccanegra is one of the most rewarding and detailed. He also focused on father-daughter relationships and the duet "Orfanella il tetto umile" from Boccanegra's first act, when he realizes Amelia is indeed his daughter, is a two-hankie affair.

Near the end of Verdi's incredible six decades in opera, he threatened to quit, but instead came up with one fresh work after another. Finally, after some two dozen serious operas, he capped it all off with a comedy. Falstaff is witty and furiously paced but with the autumnal warmth of an old man looking back on his life with a chuckle. Falstaff's Act 3 monologue is a slice of operatic heaven. Drenched from being dumped in the river (with the laundry), Falstaff muses on his fate in a cruel world. As the wine warms his immense belly in the late afternoon sun, he's revived, and the trill of a cricket (listen for it in the music!) brings a smile. Falstaff is one of three ingenious operas (with Macbeth and Otello) Verdi based on Shakespeare. The composer ends his final masterwork with a chorus of "Tutto nel mondo è burla" — everything in the world is a joke.

Read more

Children and Music

There is no downside to bringing children and music together through fun activities. We are able to enjoy the benefits of music from the moment we’re born. Although a good dose of Mozart is probably not increasing our brain power, it’s enjoyable and beautiful. From the pure pleasure of listening to soothing sounds and rhythmic harmonies, to gaining new language and social skills music can enliven and enrich the lives of children and the people who care for them.

Toddlers and Music: Toddlers love to dance and move to music. The key to toddler music is repetition, which encourages language and memorization. Silly songs make toddlers laugh. Try singing a familiar song and inserting a silly word in the place of the correct word, like “Mary had a little spider” instead of lamb. Let children reproduce rhythms by clapping or tapping objects.

Preschoolers and Music: Preschoolers enjoy singing just to be singing. They aren’t self-conscious about their ability and most are eager to let their voices roar. They like songs that repeat words and melodies, use rhythms with a definite beat, and ask them to do things. Preschool children enjoy nursery rhymes and songs about familiar things like toys, animals, play activities, and people. They also like finger plays and nonsense rhymes with or without musical accompaniment.

School-Age Children and Music: Most young school-age children are intrigued by kids’ singalong songs that involve counting, spelling, or remembering a sequence of events. School-age children begin expressing their likes and dislikes of different types of music. They may express an interest in music education, such as music lessons for kids.

Teens and Music: Teenagers may use musical experiences to form friendships and to set themselves apart from parents and younger kids. They often want to hang out and listen to music after school with a group of friends. Remember those days of basement and garage bands? Teens often have a strong interest in taking music lessons or playing in a band.

Read more

A fun lesson in how to get kids into classical music

While the merits of classical music are almost limitless, it is oftentimes a bit tricky to get kids to listen to and love it. With this problem in mind, one of our favorite experimental groups has decided to find a novel way to approach and answer the question. Take a look and listen.

By transforming contemporary pop, which kids all love, into some legendary classical compositions, the group CDZA, short for Collective Cadenza,, has taken a very fun, "spoonful of sugar" approach to the classic (ba-dump-bump!) problem. They write about this latest project:

How do you teach the classics to students today? How do you get students thinking critically about how Mozart, Beethoven, and Bach are relevant to music today? These composers provide the building blocks of modern music, and are necessary knowledge to a well-rounded musical education, but how do you get students to pay attention to these long-deceased classical music masters?

CDZA presents an innovative way to connect with students and teach them the classics.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)